Celebration of the flowers in St Aidan’s Church

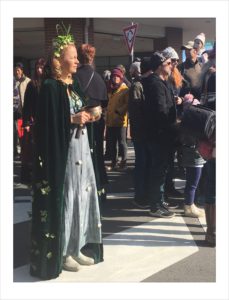

Monique Alison the Rhododendron Princess for 2018

Celebration of the flowers in St Aidan’s Church

Monique Alison the Rhododendron Princess for 2018

The Pinot Noir Study Room at Stoneleigh 50

The trees in the village are ablaze with Autumn colours. It’s like you’re in fairyland when the leaves fall around you. I walk everywhere on a scrunchy carpet of leaves.

Carloads of tourists arrive to photograph our streets. I relish feeling the dip in the seasons. We have farewelled daylight savings. The nights draw in faster and the days have a chilly bite.

Our neighbour informs us that there’s a local saying that winter arrives with Anzac Day. It appears to be true. I love Autumn – the transition season but it can also bring a melancholy with the change in light.

I’ve been living a hermit life (as much as possible with an eleven-year-old daughter) to complete my current book. My agent is really enthusiastic about the chapters she’s read. My husband, David thinks it’s the ‘best one yet’ – which is what every writer wants to hear. Technically, it’s been a challenge as I’m working with three time periods (the 1800s, 1920s and 1950). Thank you to readers who have written to me, or commented on my social media, saying how much they are looking forward to this book. The feedback means everything.

I would like to share this photograph I took in Sydney recently on an outing with my daughter to the Museum of Contemporary Art. This beautiful mer-child with the body of a child and the head of an ancient fish is called “To be carried away by the current, to be dissolved in the other.” The artist is Sangetta Sandrasegar.

The work is a comment on our changing relationship to the sea brought about by technology. Also, the disappearance of our marine-life and our move away from mythology and old sea-tales. I love her brooding power as she watches a bustling Sydney harbour and the passing clouds, unnoticed by the crowds below her. You can read more on this piece HERE. I share the artist’s thoughts on our increasing detachment from myths and nature.

I find it essential to my own balance to acknowledge seasons and moon cycles. When friends have commented on my passion for comparative religions and ritual, I think of Joseph Campbell’s quote that if you want to know what a society is like without its rituals – read the New York Times.

Here is a photo of a simple ritual my daughter and I did for the New Moon.

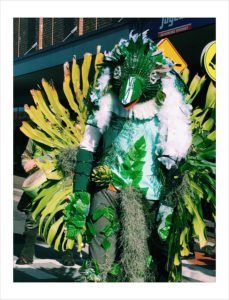

We attended our first Lithgow Ironfest which was a colour and enjoyable day with artisans, jousting, knights, battle re-enactments, steampunks and 1940s army nurses – an enjoyable contrast to the crowds and materialism of the annual Sydney Easter Show.

We’ve also been attending quite a few sessions at our favourite mountains cinema. Mount Vic Flicks is a traditional cinema experience plus the best hot soup in mugs. Once the manager even delayed putting the movie on to give patrons down the highway a chance to make the movie in time as the traffic was heavy. It’s these olde world courtesies that make our new mountain life such a pleasure.

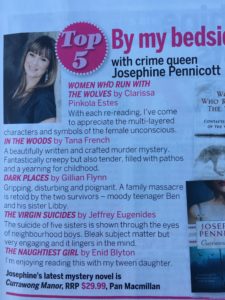

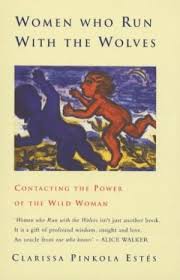

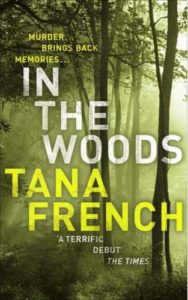

I’ve also been reading a lot. I keep wanting to have time to write a post featuring the books I’ve read this year but with trying to finish my own book at the moment it’s been impossible. But it’s a long list with thrillers and mysteries comprising the bulk. I love staring up at the stars which blaze in a way unimagined in the city. It’s so easy to let go of the trivia and dust of everyday life when you view Saturn through the telescope.

Gaiman illustrates this with the most breath-stopping testament to what we endure for stories as they in turn help us endure, by way of his 97-year-old cousin Helen, a Polish Holocaust survivor:

“A few years ago, she started telling me this story of how, in the ghetto, they were not allowed books. If you had a book … the Nazis could put a gun to your head and pull the trigger – books were forbidden. And she used to teach under the pretense of having a sewing class… a class of about twenty little girls, and they would come in for about an hour a day, and she would teach them maths, she’d teach them Polish, she’d teach them grammar…

One day, somebody slipped her a Polish translation of Margaret Mitchell’s novel Gone with the Wind. And Helen stayed up – she blacked out her window so she could stay up an extra hour, she read a chapter of Gone with the Wind. And when the girls came in the next day, instead of teaching them, she told them what happened in the book. And each night, she’d stay up; and each day, she’d tell them the story.

And I said, “Why? Why would you risk death – for a story?”

And she said, “Because for an hour every day, those girls weren’t in the ghetto – they were in the American South; they were having adventures; they got away.

I think four out of those twenty girls survived the war. And she told me how, when she was an old woman, she found one of them, who was also an old woman. And they got together and called each other by names from Gone with the Wind…

We [writers] decry too easily what we do, as being kind of trivial – the creation of stories as being a trivial thing. But the magic of escapist fiction … is that it can actually offer you a genuine escape from a bad place and, in the process of escaping, it can furnish you with armour, with knowledge, with weapons, with tools you can take back into your life to help make it better… It’s a real escape – and when you come back, you come back better-armed than when you left.

Helen’s story is a true story, and this is what we learn from it – that stories are worth risking your life for; they’re worth dying for. Written stories and oral stories both offer escape – escape from somewhere, escape to somewhere.

We are now back in Sydney, still reflecting over Heron Island’s turquoise sea and sky, and the ever-gliding shadows in the ocean of sharks, sting-rays and turtles.

Heron Island, one of the great natural wonders of the world, is a coral cay which began forming around 6000 years ago. Situated off the Queensland coast, Heron has been described by David Attenborough as one of his favourite places to see marine wildlife up close. The island is small; it takes about 20 minutes to walk it (double that time when we were with our ten-year-old daughter at night on our turtle hatchling expeditions). We chose Heron to retreat and recharge because there’s no technology there and we were all longing for a break from Wi-Fi and computer screens. Plus, it was turtle hatching time and who can resist baby turtles born in the wild?

I miss circumnavigating the island’s white sands. I loved being in that world of primary-coloured crayon blue sky and sea. If I close my eyes now and attempt to block out the traffic and the workmen’s constant drilling from the factories surrounding me, I can hear a faint lapping of water, and feel within me the elegant unexpected beauty of a turtle swimming past and the graceful otherworldly shapes of the stingrays in their exquisite ocean glide.

I have emerged like the little mermaid from Hans Christian Andersen’s tale from an enchanted underwater world of coral forests, exotic fish and – onshore – luxuriant green foliage that parasolled us overhead in a magnificent jungle. Heron Island is home to up to 100,000 birds. At night the shearwaters return from the sea and the calls to their waiting children sound like the eerie screech of restless, uneasy ghosts.

We wandered for five days in a tourist postcard of Australia, marvelling over this parallel tropical world as we swam with reef sharks and stingrays. We even saw a manta ray on the semi-submersible boat tour of the reef.

As Daisy and David snorkelled out trying to find sharks, I was paddling around knee deep trying to avoid them (the sharks). Then I realised I was surrounded by what looked like twenty fins. For years I’ve had a severe shark phobia, but once you’ve experienced them around you and realise these reef sharks are not interested in you as dinner, then you form a new respect towards these elegant and fascinating beings.

We cheered on baby turtles as they hatched, making their plucky and courageous dash to the ocean. Some sadly were snatched instantly by the waiting sharks, but others were taken by the current to hopefully travel the world before they miraculously return to their original hatching place.

Daisy loved the Junior Rangers programme and made good friends amongst the children there. They called themselves The Clan and bonded immediately over turtles hatching and snorkelling with sharks. Daisy is still thrilled she managed to snorkel with her new friends out to the shipwreck that serves as a breakwater.

Walking on the beach one night, my daughter cried out as a baby turtle fell from the sky at her feet, obviously dropped by a bird. We watched in awe as it managed to upend itself the correct way and continue its journey to the sea. My daughter christened that turtle Lucky and we vowed to return at the same time in 30 years to see if Lucky would return to her original hatching place.

It’s hard to believe that in the 1920s Heron Island was a turtle cannery and in the 1950s tourists rode the turtles for sport. Thankfully, turtle riding was outlawed circa 1960.

And so we are back in Sydney. The jackhammers are jarring as the workmen dismantle the shoe factory next door to make yet more flats and shops. The city seems a grotesque heavy charcoal drawing next to the primary-coloured island with its pristine air and breathtaking scenery.

I hope it is not too long before we make that journey over the sea to Heron Island and enjoy the island’s “Welcome” cocktail. I watched Heron disappear from the boat as we left, farewelling sadly that magical coral cay with its turquoise waters and sea life until it became a distant faint smudge on the horizon.

I could have sat on the sand forever watching the marine life circle the island, listening to the call of birds and staring into the shimmering dramatic blue that stretched forever. But I should feel lucky to have seen it at all.

It’s been sobering learning from the guides on Heron Island about how the impact of global warming and mankind’s impact has had a noticeably detrimental effect on the reef. We are all part of the same web and, as legendary marine biologist and oceanographer Sylvia Earle warned in the papers this week: “If you like to breathe, listen up, the message is to protect the ocean as if your life depends upon it, because it really does. No ocean, no life. We’re so concerned about the green movement, but without the ocean, there’s nothing there. No blue, no green.”