I know I am deathless…

Walt Whitman, ‘Song of Myself, 20 – from The Book of Sand

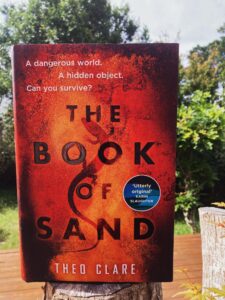

This was never going to be an unbiased review as I was friends with the author of The Book of Sand. Even though I rushed to preorder, I was tentative about reading it when it arrived. Would it be too distressing because of Clare’s recent death in 2021? As a huge fan of her Jack Caffery gritty crimes and standalone novels under her pseudonym Mo Hayder, would I be able to enter the world of her fantastical fiction?

I needn’t have worried. The Book of Sand is a joyful reading experience. I devoured it over a few nights and truly didn’t want it to end. It can’t be compared to any of Clare’s previous work as it stands on its own unique legs and roars. Clare could have continued writing her Jack Caffery dark crimes – she was top of her game – but this series demanded to be birthed and it’s obvious by its exuberant tone that she loved creating it.

The story is set between two seemingly disparate worlds. The Cirque is a sand world where the Dormilones, a group of individuals of varying ages, incomes and faiths from different places on Earth (Sri Lanka, Stockholm, Paris, Jaisalmer, Great Britain) connect with the disconcerting feeling they already know each other. The Family aren’t biologically linked but have been summoned to the Cirque on a quest to discover the Sarkpont under the guidance of the mysterious Mardy. Mardy informs them they have twelve chances and twelve Regyres without revealing much more information. The group face all the challenges of a sand desert as well as the sinister and dangerous Djinni who hunt on the second night (known as the Grey Night) when the family have to ensure they are safely enclosed. Other family groups are also competing for the Sarkpont and are prepared to fight to the death to win. Failure to locate the Sarkpont after twelve tries will result in a consequence so horrible the Dormilones team leaders cry when Mardy reveals it to them. Time is different in the Cirque. Days pass there as years pass on Earth. Travellers known as Scouts are sent out to different time periods back to Earth. No Scout knows what country or year they will arrive in when they transition to Earth. The only constant they have is that they will always die there and will return to the Cirque. Scouts can pass each other on the street in Earth and not recognise each other. Balzac is mentioned as naming the Virgule in the Cirque. When he was in Earth, he was driven mad, possibly by his vague memories and connection with the Cirque.

The second world is set in contemporary America in Fairfax County, Virginia, the home of teenager Mckenzie Strathie, a high achiever who feels alienated from her family and peers and is haunted by longings for the desert. A lizard appears in her bedroom, a woman in a sari talks to her from a tree, and a high school science fair experiment involving the lizard goes disastrously wrong. Then a stranger texts her that he too can see the lizard when nobody else can. Mckenzie is taken to a therapist but begins to suspect the motives of the people closest to her. The dual worlds begin to snake together in a surprising twist.

I love the visual images shimmering through the book. Spider, head back screeching in triumph into the hot desert air, his petticoat blowing around him as he rides his Sandwalker. Mardy, in her bobbly pink cardigan covered in cats. Desert sunsets and sunrises with their brilliant colours ranging from the grey-pink of a dead rose petal into clear shocking blue.

The sand world, an eerie distorted mirror world of Earth, has McDonalds, deserted petrol stations, a can of Sprite Zero suddenly appearing. Meals of kangaroo haunches, mutton, ears of corn, sheep cheeseburgers, date wine and a bong filled with ganja. It’s a strange and terrifying visual weave of dreams and consciousness.

The Djinni, or as Amasha calls them – the hungry ghosts – are malevolent and mysterious. Their faces are described as small, fat and pink, like a white human baby; they are stick-thin, white and much taller than human beings. They rip bodies to pieces in seconds when they encounter them in the Grey Night. Some of the Dormilones believe even uttering their name summons trouble. They are the fallen angels of this world. “God ye shall know, yet falleth the Angels so fast.”

Cross Alice in Wonderland with a Tarantino movie and The Hunger Games and you still can’t come close to describing The Book of Sand.

Clare first told me she was writing a book vastly different to her dark crimes in 2017, when we met up Avebury, UK. I excitedly wanted to know what it was about and she laughed in her mischievous way. ‘It’s weird,’ she said. It is indeed wonderfully weird – and wonderfully clever.

Like all the best fantasy, The Book of Sand examines major life questions – faith and religion, who we are and where we go when we die, the inner knowing that the world we inhabit is not our true home and the blood tribe we are born to may not be our true family. Death is not an end but a transition that happens repeatedly.

At the time of writing, Clare had no idea her own death was so tragically near but there are so many references to transitions and other states of consciousness throughout the book that it’s impossible not to think a part of her being knew.

Readers of her graphic crime books won’t be disappointed with the energy and heat of her fight scenes. There are severed ears, scalpings, unexpected shocking deaths, mutilations and one of the characters (no spoilers) dies a very sad death. I actually had to skip those paragraphs as I couldn’t cope with it.

When I reached the end, I had expected to be emotional. The tissues were ready but instead I felt a deep peace. I couldn’t stop smiling. I was – and will always be – awed by her vision, courage and talent. I’m so relieved to hear Clare finished other books in this dynamic series and I can’t wait to rejoin the Dormilones as they continue their quest.

The Book of Sand is dazzling, lyrical, surreal and a beautiful legacy to Clare’s legion of fans by a brilliant, totally original gutsy woman.