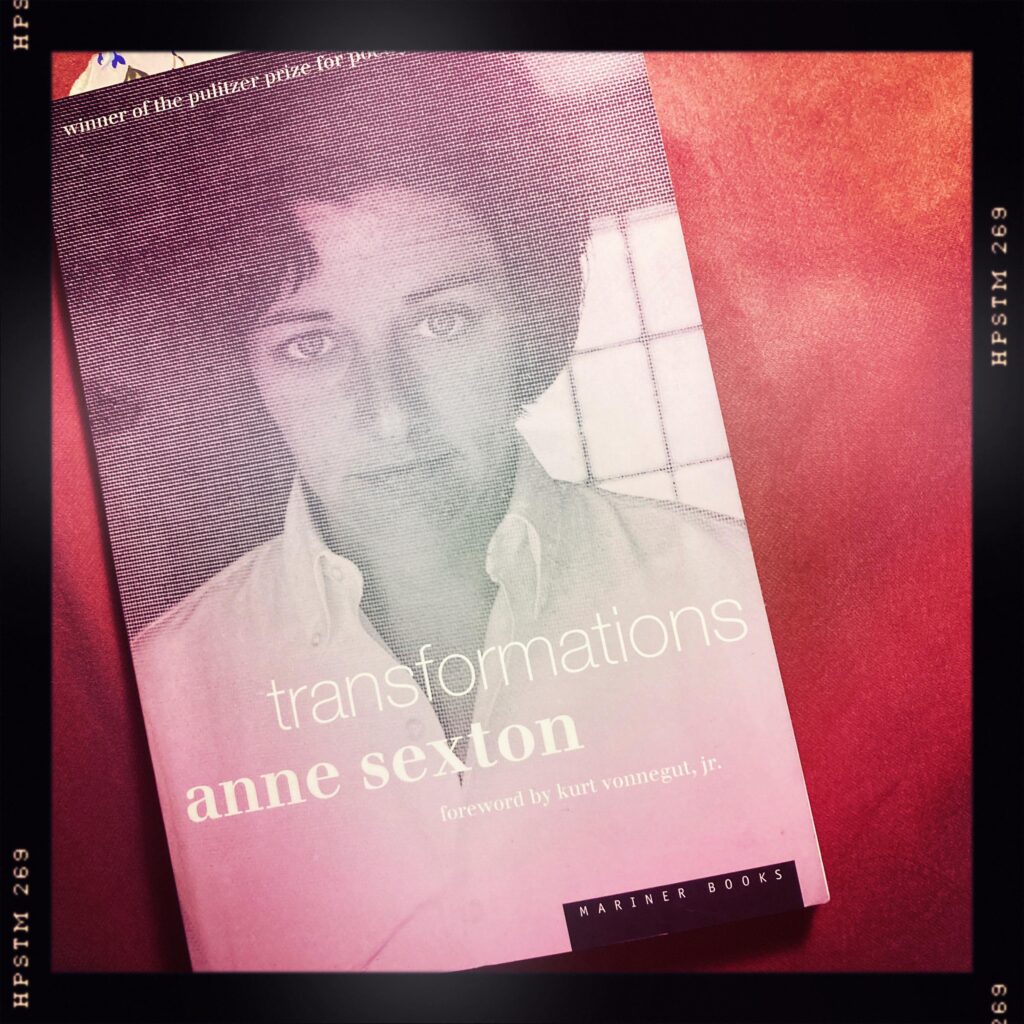

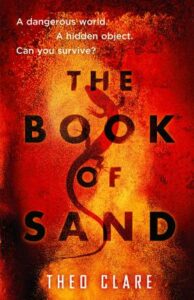

For National Poetry Day, a tribute to Anne Sexton and her brilliant poem, “Cinderella” from the book Transformations which I’ve been reading before sleep to guarantee disturbing dreams.

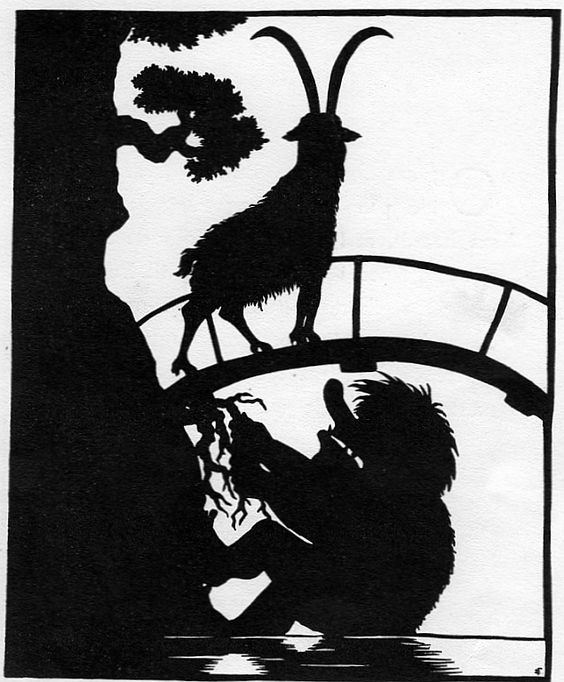

You always read about it: the plumber with the twelve children who wins the Irish Sweepstakes. From toilets to riches. That story. Or the nursemaid, some luscious sweet from Denmark who captures the oldest son's heart. from diapers to Dior. That story. Or a milkman who serves the wealthy, eggs, cream, butter, yogurt, milk, the white truck like an ambulance who goes into real estate and makes a pile. From homogenized to martinis at lunch. Or the charwoman who is on the bus when it cracks up and collects enough from the insurance. From mops to Bonwit Teller. That story. Once the wife of a rich man was on her deathbed and she said to her daughter Cinderella: Be devout. Be good. Then I will smile down from heaven in the seam of a cloud. The man took another wife who had two daughters, pretty enough but with hearts like blackjacks. Cinderella was their maid. She slept on the sooty hearth each night and walked around looking like Al Jolson. Her father brought presents home from town, jewels and gowns for the other women but the twig of a tree for Cinderella. She planted that twig on her mother's grave and it grew to a tree where a white dove sat. Whenever she wished for anything the dove would drop it like an egg upon the ground. The bird is important, my dears, so heed him. Next came the ball, as you all know. It was a marriage market. The prince was looking for a wife. All but Cinderella were preparing and gussying up for the event. Cinderella begged to go too. Her stepmother threw a dish of lentils into the cinders and said: Pick them up in an hour and you shall go. The white dove brought all his friends; all the warm wings of the fatherland came, and picked up the lentils in a jiffy. No, Cinderella, said the stepmother, you have no clothes and cannot dance. That's the way with stepmothers. Cinderella went to the tree at the grave and cried forth like a gospel singer: Mama! Mama! My turtledove, send me to the prince's ball! The bird dropped down a golden dress and delicate little slippers. Rather a large package for a simple bird. So she went. Which is no surprise. Her stepmother and sisters didn't recognize her without her cinder face and the prince took her hand on the spot and danced with no other the whole day. As nightfall came she thought she'd better get home. The prince walked her home and she disappeared into the pigeon house and although the prince took an axe and broke it open she was gone. Back to her cinders. These events repeated themselves for three days. However on the third day the prince covered the palace steps with cobbler's wax and Cinderella's gold shoe stuck upon it. Now he would find whom the shoe fit and find his strange dancing girl for keeps. He went to their house and the two sisters were delighted because they had lovely feet. The eldest went into a room to try the slipper on but her big toe got in the way so she simply sliced it off and put on the slipper. The prince rode away with her until the white dove told him to look at the blood pouring forth. That is the way with amputations. They just don't heal up like a wish. The other sister cut off her heel but the blood told as blood will. The prince was getting tired. He began to feel like a shoe salesman. But he gave it one last try. This time Cinderella fit into the shoe like a love letter into its envelope. At the wedding ceremony the two sisters came to curry favor and the white dove pecked their eyes out. Two hollow spots were left like soup spoons. Cinderella and the prince lived, they say, happily ever after, like two dolls in a museum case never bothered by diapers or dust, never arguing over the timing of an egg, never telling the same story twice, never getting a middle-aged spread, their darling smiles pasted on for eternity. Regular Bobbsey Twins. That story.